So we have decided to face another monster and this time it probably won’t be only some kind of. If you don’t know anything about the Annapurna Circuit, read on. You will learn about it bit by bit. The Annapurna Circuit is one of the most popular hiking treks in Nepal and probably in the world. However, not many people do it by bicycle for obvious reasons: It is a hiking trek. But usually an easy one. That’s not only because there is no climbing involved, but also because there are plenty of lodges along the trek. So you don’t need a tent or a camping burner. At least that’s good news for us, and we decide to leave most of our equipment in Kathmandu at Madhukar’s place. Madhukar is the warmshower host of Max and he will store our equipment while we are on the trek.

Unfortunately we cannot get the Annapurna Conservation Area Permit (ACAP) and the TIMS-Card (Trekkers Information Managemant System) in Kathmandu and we are told they are double the price on the trek. But we sit in the bus towards Dumre.

Day One – Easy like Sunday morning

We arrive in Dumre at 11:30 am and stand on 400 m above sea level. Within the next few days we will cycle along the longest uphill on our journey. According to the paper map we bought, Thorong La – the highest point on the Annapurna Circuit – is „the biggest pass in the world“. Yeah, whatever that means.

Our goal for today is Besisahar, a little town directly at the entrance to the Annapurna Conservation Area (ACA). There we will get our permit and the TIMS card. Without the bags and on paved road we feel like angels flying up a mountain. Within a few hours we arrive in Besisahar and find a very nice guesthouse. Not having a tent feels strange, though. We are heading into the mountains and totally rely on lodges.

Day Two – The standards drop

The first thing we do is getting our TIMS card. The TIMS cards is one useless piece of paper. It contains all our personal data and the route we are taking. It is not for us. It is for the mountain rescue in case we get lost in the mountains. That way they know who is up in the mountains and who they have to look for in case of an avalanche or worse. We also have to write down our insurance number and are told to have a credit card with us, otherwise the helicopter will take us out last.

After all that doesn’t seem too useless, but we already had to write down the exact same information for the ACAP. But in the end they have a good reason for that:

The Annapurna Circuit Disaster

On October 14th 2014, just a year ago, Cyclon Hudhud was approaching Nepal. Within a few hours the temperatures dropped rapidly and one of the worst blizzards in Nepal’s history covered everything under three meters of snow. The result was Nepal’s worst mountaineering disaster ever. 43 people died on the Annapurna Circuit. 175 were injured, 45 still missing after a week. Hundreds had to be rescued with helicopters after they endured days locked in the mountains. Also a lot of local shepherds died. We have heard about this disaster and therefore checked the weather forecast several times. It always said 10 days sunshine in a row. Not a single cloud. However, you might say: „But the weather changes quickly in the mountains and those people in 2014 checked the weather forecast as well. In the end it didn’t help them„. We thought the same, but apparently people don’t learn anything, no matter how often you tell them that the mountains are not a playground. In fact the weather forecast had warned about Cyclon Hudhud one week in advance. But even with an internet connection available above 4000 m altitude, people just didn’t check the weather forecast. Even the locals didn’t. And most important: Not even the officials. There is a checkpoint in every second village, where you have to show your permit, but apparently nobody stopped people to continue going up into the mountains even though a blizzard was approaching. And within the next few days we will meet people that have no idea about the weather even above 4000 m. They just see a cloud free sky and start hiking in the early morning. And local shepherds wear flipflops on 4200 m altitude. Probably because they want to show off. Why do all these people drive cars with airbags and wear a helmet on the motorcycle? It just makes no sense at all.

We have all the paperwork done at around 10:30 am and finally leave Besisahar. By the way the permit and TIMS card were the normal price. Immediately at the end of the village our standards drop. The worst roads of the Pamir highway would be just fine now. As long as we can cycle it is a good road, no matter how much of a bone crusher it is.

We miss a bridge and end up on a hiking trek. After around 2 km we turn around and go back to the „main road“. Along the road we see a lot of lodges and restaurant, so we don’t feel uncomfortable without a tent any more.

We arrive in Syange and find a nice guesthouse. The prices are ridiculously low. Some lodges even offer rooms for free in case you have dinner at their restaurant. After taking a shower and having dinner, we want to get our bicycles into the house, which are still standing on the road. We cannot see them from the restaurant because a bus is standing in front of them. That’s correct: There is a bus on the road. We have no idea how a bus is regularly running on that road. It is not a road. It is some rocks. It is something without plants in the way.

Day three – No doubt…?

The next morning we learn, that the last bus stop in fact is Syange. So from here on there are only some 4WDs, some trekkers and the two of us. Because this is not Pamir highway. We don’t see any other cyclists. This is not a cycle route. The „road“ is still doable up to Chamje most of the time, but after that it is getting worse. Soon it gets so steep we both have to push the bicycles a lot. From time to time I wonder how even a 4WD can drive here. The road construction, however, is impressive. Often it is dug into the rock, and waterfalls, creeks and rivers are crossing it. The landscape is also beautiful, though still very tropical, green and humid.

For hours we push the bicycles and the first doubts arise. „This is not going to be easy“, Kyla and Didier told us. But we are still on a low altitude, around 2000 m, with plenty of oxygen. When they talked about „very steep“ parts of the trek, they never mentioned this one. We agree to make it to Manang, no matter what. Manang is a village on 3500 m altitude. After that even the 4WDs cannot continue. It should be the last village before things get serious.

That day we make it to Danagyu. The evenings are getting noticeably colder so we sit in the kitchen while the host is preparing dinner for us and two hikers: Adam from Scotland and Tom from Israel. Both on the same trek as we are, only without bicycles.

Day Four – Beauty

The day starts with steep and bad road, but is even more rewarding than the day before. The road winds up narrow valleys, still dug directly into the rock most of the time. We stay away from the side of the road, because without any barrier you can easily fall down a few hundred meters until you finally hit the beautiful but wild river which has carved the valley for the last couple of million years.

Amazing waterfalls fall down on the other side and further beneath the road easily pushing tons of water down the valley within seconds. We often take breaks to enjoy the landscape.

From time to time, Tom or Adam is passing us. When the road is good we overtake them again. We meet both of them shortly before we arrive in Pisang. Tom wants to make it to the same guesthouse, but doesn’t show up that evening. We wonder why. The room this night is only 100 Rupees (less than one Euro). We sit together with the host in the kitchen. She prepares dinner on a wood fire and we start to talk with her. Although the Annapurna Circuit is one of the most popular and most touristic treks in Nepal, we don’t see many tourists. We already know, that the shortage of petrol has lead to fewer tourists. Also the Annapurna Circuit Disaster probably frightened some, who otherwise thought the Circuit is an easy walk (that’s how it is described in the Lonely Planet). But apparently the earthquake just a few months ago had the worst effect on tourism. A lot of people – like us – are totally misinformed. We were told to leave the Nepali people alone, so they can rebuild their houses. While this is absolutely true, the area worst affected by the earthquake is actually the Langtan valley north of Kathmandu. Along the Annapurna Circuit the earthquake had little to no effect. People desperately want more tourists, but they stay away – ironically to help the Nepali people. So they fight for tourists by offering their rooms for free. Anyway, we like the situation to some extend, because the Annapurna Circuit is usually as crowded as some Danube cycle route in Austria during summer. But not now. The villages seem like ghost towns with lots of empty lodges.

Day Five – The white knights rise

We leave Pisang and the road is again incredibly steep. After a while, when we can easily cycle we overtake Tom. He had a very rough night, because he didn’t make it to Pisang before sunset. In the dark he couldn’t find the little track that leads away from the main road and into the village. So he actually spend the night outside with only a sleeping bag and not even an insulating mattress. Pisang is at 3200 m, so you can imagine, that the night was cold. I remember taking a shower last night and how steam was all over my body, because the cold water vaporized on it. Tom has no GPS, is badly equipped and knows little about the weather. He is a nice guy, we hope he is equally lucky in the days to come.

We reach Humde at around 10 am. Humde is the last airport up here in the mountains. Of course only a small airport for little planes. The village itself is dead, not much going on here. But from now on, the Annapurna mountain range with its white giant knights gets more and more visible. One of the first mountains we can see is Tilicho Peak (7134 m). We arrive in Manang (3500 m) with slight headache and little appetite. Clear symptoms of:

Altitude Sickness

We have had experience with altitude sickness already on the Pamir Highway. Since the Annapurna Circuit reaches a way higher altitude at Thorong La, we took it even more seriously this time. The symptoms we had in the Pamirs were nausea, headache, a hard time to sleep at night, tiredness and weakness and one time I felt slightly drunk, which is clearly an indicator not to move up any further. Altitude sickness is very serious and can easily be fatal. Again lots of people ignore all physical signs and also all free information given by medical staff along the Annapurna Circuit. All while hiking alone, with no one to help them find the way down in case the symptoms get worse. Again this is just ridiculously stupid, but people apparently don’t care. Ambition is everything. I recommend doing some bungee jumping in Pokhara, if you really like the thrill.

So we decide to stay in Manang and see how the symptoms improve overnight. I immediately have a short nap in the guesthouse. We eat something, then go to bed at 6 pm and sleep for 12 hours straight.

Day Six – Separating the wheat from the chaff

When we wake up in Manang we feel absolutely good and strong and ready to move on. Several small villages are along the track the next 30 km, so we can stop anytime. We also check the weather forecast a last time in Manang. There is a print-out hanging in the ACA office and in the medical station. Leaving Manang feels strange because we now leave the road. From now on, we are the only cyclists on a hiking track. Behind us, Annapurna II, Annapurna III, Annapurna IV and Gangapurna (7555 m) remind us, that this is truly the Himalaya.

Easily 30-50m of snow is stacked on top of each peak and enormous glaciers seem like the unbreakable harnesses of these majestic knights. We have clear blue sky. Some hikers started already, others are leaving Manang together with us. The silence is loud. Everybody is concentrating on the track. The air is getting thinner. We arrive in Gunsang within an hour and actually want to stay there already, because we really want to make sure we are acclimatised well all the time. We already asked for a room, when we decide to move on.

We both are feeling absolutely fine and it is still early in the morning. The path to Yak Kharka is good most of the time. We can cycle a lot on a perfect single trail and arrive in Yak Kharka only two hours later. We haven’t gained much altitude since Gunsang and so we decide to even try to reach Letdar. The track gets steep, then again a perfectly fine single trail and finally another steep part until we eventually arrive in Letdar. It is only 2:30pm, so enough time to make it to Thorong Phedi, but we are now on 4200 m. That’s 700 m higher than Manang and definitely enough for one day. We need to acclimatize.

Day Seven – Into thin air

We didn’t sleep well in Letdar, but otherwise feel good and ready to move on. Even less hikers are on the trek. Previously talkative people stay quiet now, the groups are slowly stepping up the hill, taking breaks after every steep part of the trek. After two hours we reach Thorong Phedi on 4560 m. Even though there is enough room for hundreds of people it seems more like a camp. There is a satellite telephone and a medical first aid station for immediate treatment of altitude sickness. Some of the hikers smoke cigarettes. Some have no idea on which altitude they are. Some still don’t know the weather forecast. Or pretend not to know, because it shows what a great adventurer you are. Again we decide to stay here. The weather is still good for more than 5 days so we are not in a hurry. We have some sort of a brunch. The higher we get the cheaper the rooms, but the more expensive the food. A big pot of tea (2 Liters, you have to drink a lot to prevent altitude sickness) was around 3$ in Syange and is now above 10$. Charging your cellphone for an hour is 60 cent. However, there is of course no mobile network up there. After brunch we take another hour break. It is still early and some people continue to Thorong High Camp. As the name implies it is getting serious. High Camp is on 4900 m. The path seems extremely steep and that’s exactly what Didier and Kyla told us. Also the map shows one hell of a climb. At around noon we decide not to stay here and continue pushing the bicycles. Until now it mostly depended on your mountain biking skills, whether you could cycle or not. That’s over. This part is even hard to push the bicycles. After half an hour we set a new record, since we are now higher than Akbaital Pass in Tajikistan (4655 m). We continue along one of the most difficult paths I have ever been on.

Dieser Weg wird kein leichter sein

Dieser Weg wird steinig und schwer

Nicht mit vielen wirst du dir einig sein

Doch dieses Leben bietet so viel mehr.This path won’t be an easy one

This path will be stony and difficult

You won’t be at one with many

But this life has to offer so much more

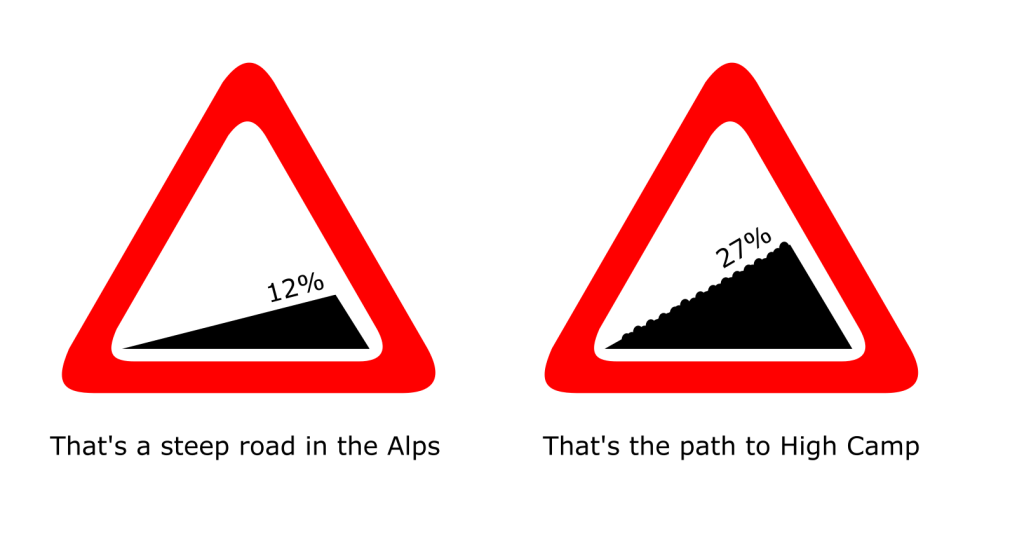

No time for a single picture. We have to concentrate not to slip while pushing our bicycles up. In the end we arrive at Thorong High Camp after less than two hours of pushing. We climbed up 440m within a distance of 1.5km. That’s crazy. Let’s do the math:

27% is the average. The steepest road in the world is Baldwin Street in New Zealand with 35%.

Me and my bicycle is the mass (m): 80kg + 40kg = 120kg

From Thorong Phedi to High Camp is the height (h): 440m

Gravity (g) on Earth is constant: 9.81m/s²

So the energy needed to move the bicycle up from Thorong Phedi to High Camp equals m*g*h. That’s 517968 Joule (W) or 123797 calories.

We made it from Thorong Phedi to High Camp in approximately 1 hour and 45 minutes. That’s 6100 seconds (t). Since power (P) equals work (W) per time (t), we get 85 Watts. Since we moved from 4560m to 4900m we spend our time on an average of 4730m. The amount of oxygen on 4730m is 80% of the amount of oxygen on sea level. If we take this into account we had an average power of around 106 Watts. And since pushing a bicycle up a sandy, rocky path is not really laboratory conditions, you could easily double the effort. So that’s around 200-250 Watts. That’s 0.34 horse powers or four notebooks running at the same time. Just so you know….and because I like numbers.

Day Eight – High five

We get up at 5am. I step out of the ice cold stone hut. It is still pitch black outside. I see lights moving up the mountain. The first trekkers have left Thorong Phedi at 3am and just now arrive at High Camp. They will continue to Thorong La, the Thunder Pass. We first have breakfast and wait for the sun to rise. Because we already know, that the first few hundred meters of the path to the pass is icy, very narrow and on a very steep hill.

So at least we want to see something. We carefully push along the path. The icy part ends. The next section is extremly steep and narrow. The lack of oxygen sucks big time. 10 steps, 10 seconds break. Every few minutes we take a longer break. After those breaks I feel almost unable to move. Only after I move on it starts to get better. Again ice on the path. Some Nepali porters help us carry the panniers for a few meters, so we can concentrate on pushing the bicycles. It is dangerous, it really is. It is not life threatening, but the bicycle would definitely slide down very long and falling would mean hurting yourself in one way or another. After an hour it is time for a high five. We just crossed the 5000m mark. There is still 416m on top of that and in front of us. We slowly make it to 5200m. The silence is frightening….the lack of oxygen scary…..we are all alone….except this little tea house! What? The snickers is too expensive, but we have some tea. Somehow reminds me of this:

Reinhold Messner is one of the most famous alpine climbers in the world. In this show they played a prank on him by putting a kiosk on one of his favorite routes on Matterhorn, since he is a critic of touristic exploitation of the mountains.

A Canadian guy who had already have a heavy cough in High Camp almost breaks down. He can hardly breathe. Within 20 minutes the porters bring a pony. They decide to take the guy up to the pass, because it is faster to reach a hospital on the other side.

Then we leave the tea house. The slowest hikers have overtaken us. Even the guy on the pony is getting smaller in the distance. We are all alone. We have plenty of time and we repeat this like a mantra. Plenty of time. Plenty of time. Om. Plenty of time. We will make it to the top. Sooner or later. Plenty of time. Plenty of time. Om.

Unfortunately there is not plenty of oxygen and it is an unpleasantly unreal place to be. Nobody around, total silence, only the sound of yourself heavily breathing and your shoes seeking some grip in the rocky, dusty ground. No sign of the pass. Only in the distance a very slow group of hikers takes a long break every five minutes. But we are taking even longer breaks every three minutes. It is a stressful situation and pretty difficult to handle. The lack of oxygen not only makes you feel weak like a 90 year old, it also makes you feel miserable as a whole. At the mediteranean sea, this wouldn’t affect you at all. But above 5000 m altitude you somehow have this urge to feel perfectly fine. We say hello to Mr. Doubt who was pretty quiet the last couple of days. Now he starts repeating this one annoying sentence over and over again: „I doubt you can make it to the top“. Also Mrs. Panic passes by, muttering something like „We won’t make it. It’s getting too late. Nobody will find us“. We wave her goodbye and continue. Step by step. We have plenty of time. Prayer flags are waving in the wind. This must be the pass! It isn’t. The GPS says just another 60 m in altitude. No pass in sight. We really struggle. Another steep climb. Do you remember: We are still pushing bicycles! Suddenly a guy is approaching us from the other direction. He says, the pass is just around the corner. We know, but how long will this corner be? He gets out his camping burner and prepares some tea. Alright, some people have spent too much time up here. We don’t want tea, even though he seems to be British. Then some colors. More colors. Prayer flags. People. We have plenty of time. Finally, for the last few meters, the path gets flat. I jump on my saddle and cycle to the top of Thorong La at 5416m. The Koreans, who have followed us the last days, are all standing on top, applauding, taking videos of us. During the last days we have become some sort of celebrities. With the last oxygen I shout: „We could cycle all the way up!“. Then I fall from the bicycle.

We did it. It is 10:30 am and after four and a half hours we are standing on 5416 m, the highest elevation we will probably ever stand with our bicycles. This is Thorong La, the Thunder Pass, situated on a higher elevation than Mount Everest Base Camp. We are thunderstruck. Within 8 days we have cycled and pushed our way 5000 m uphill from Dumre to this point. Some porters seem to be all bored, having some tea, because there happens to be another tea house standing on top of the pass. Go ahead, tell me how touristic this pass is and what an easy walk. We cycled! I am done! We pushed to the limit.

Lala lalala, la la lalala! – Self esteem

Now why am I talking about self esteem? It is not because we managed to make it to Thorong La. You could as well easily call that stupid. I have a totally different reason for that. I have mentioned several times, that we have been sick again and again in Central Asia. Cora had to suffer a lot of pain in Tadjikistan and often believed she did a bad job on the Pamir Highway. I was also suffering from severe symptoms and we didn’t really know what was going on with us. We couldn’t really rely on our bodies. Why did we stay sick all the time while others had only short periods of illness? Cora got the right treatment in Almaty. I finally got the right treatment in Hapur at the Sikh Temple. Apparently it was the gardia amoebe that is common in Central Asia and that has made our life constantly miserable for almost three month. Without these symptoms we could attempt Thorong La and finally made it to the top without too much trouble. We could purely concentrate on this exhausting trek, which to some extend turned out to be often easier than the Wakhan valley in the Pamirs. So today we regained much of our self esteem and know what we are really capable of.

But standing on top of the pass is not the end of this day. We now have to push down a terrible 1600 m of altitude to finally arrive in Muktinath at dusk. What an extraordinary day. We get apple crumble, a yak burger and a pizza full of yak cheese. We are still on 3800 m.

From Muktinath it takes us four days to finally reach Pokhara. On the way, the oxygen is coming back and below 2500 m we feel all good again. The road stays very bad up to Beni and our bicycles suffer a lot. We enter Pokhara from another direction as previuosly and find the real Pokhara away from all the touristic places. We enjoy it a lot this time. It is now end of November, the season is almost over. The shortage of petrol is still an issue and it is getting colder. There are not many tourists. We get cake in the German bakery and finally take the bus back to Kathmandu. Looking back the last 14 days seem like a dream. But it also gives me a chill knowing this dream has become a nightmare for others. No matter what, we are in a safe environment again. Right now I am sitting on the porch of our warmshower host Madhukar. Plenty of people, plenty of oxygen. Tomorrow we will get our visa for Myanmar, and then quickly have to leave Nepal, because our visa expires in just a few days. So everything is back to normal, except one thing. Our mantra is getting harder to believe:

We have plenty of time

Es ist der Wahnsinn!! Glückwunsch zu dieser Leistung und dem atemberaubenden Blog-Eintrag. Ihr könnt mit Fug und Recht stolz auf Euch sein. Man kann Euch für Euren Mut und Euer Ausdauervermögen nicht genug Respekt zollen und Euer Blog ist einfach SPITZE!!

Hammerding! Glückwunsch zu dieser Etappe, klingt nach nem Peakpoint! Schöne Bilder! Macht Spaß sowas zu lesen.

Eurasischer Peakpoint auf jeden Fall.

Wen you head out to climb Aconcagua in Argentina you also need these permits. But in addition to the papers they hand you some plastic bags. And you are ment to bring them back filled, not with your plastic waste, this you have to carry home anyway. You have to bring your „human waste“ back. Not a pleasant duty for yourself, but makes the place look more „untouched“ for the ones that come after you.

Sounds strict but effective. Annapurna is full of plastic bottles. People could easily take them down but have no bags to carry them.